Travel Stories

Women in the Wild

April 23, 2024

Your Ultimate Guide to Antarctica

April 9, 2024

The Unexpected Impressions of Greenland and Wild Labrador

April 4, 2024

Our Guiding Lights: Meet Our Inspiring Tour Guide Yasmine from Egypt

April 3, 2024

How Tourism Supports Local Women in Morocco

April 2, 2024

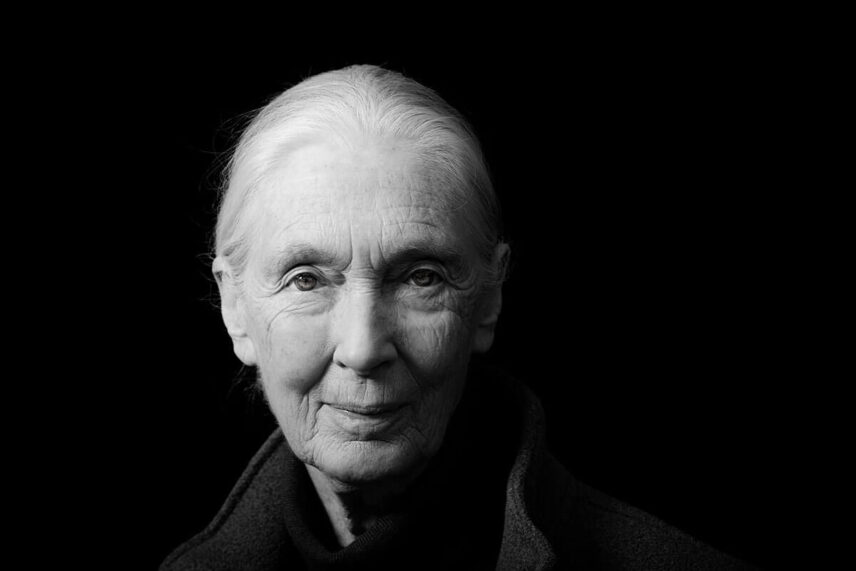

Jane Goodall: Hope for Humanity

March 28, 2024

Your Ultimate Guide to the Northwest Passage Expeditions

March 25, 2024

The Quiet Rapture of the Northwest Passage

March 22, 2024

Prepping for Scotland: A Guide to the Secret and Surprising Side of this Country!

March 18, 2024