I was born in Norway, into a family shaped by distance, weather, and the daily discipline of paying attention. My father was a captain in the maritime industry. My mother was Norway’s first female wireless operator, sending and receiving signals across dark oceans long before communication was easy or forgiving. From both of them, I learned early that awareness is not optional, skills, training and precision matter. And the North is not something you romanticize- it is something you learn to read and understand.

Svalbard sits at the far edge of that inheritance.

This Norwegian archipelago, suspended between mainland Norway and the North Pole, is one of the northernmost inhabited places on Earth. It is not simply “the Arctic.” It is specific, regulated, monitored, inhabited, and alive. You feel that immediately when you arrive in Longyearbyen. There are no trees. No casual wandering outside of town without protection. Weather, ice, and wildlife set the terms, and that immediately makes you pay attention.

I first came to Svalbard in 2013, working as a guide on an expedition ship. I had already spent decades in polar regions, including Antarctica, but Svalbard pierced me differently. Antarctica humbles you through scale. Svalbard does it through proximity. It is close. It feels as if it is a mirror shining a light on who we are and what we care about.

Over the years, as I returned regularly to Norway to visit my father, that connection deepened. Norway’s culture-its humble restraint, its relationship with nature, tradition, and quiet confidence- this slowly became part of how I move through the world. On my wall hangs a painting by Svalbard resident Ole Storp called PolarNatt, given to me by my father. It reminds me to slow down, to look longer, to trust what reveals itself gradually. Svalbard feels exactly like that painting.

Women Who Stayed When It Was Dark

From the early twentieth century onward, women were present in Svalbard as trappers, scientists, writers, and workers, meeting the same conditions and consequences as anyone who stayed.

Wanny Wolstad came to Svalbard in the 1930s as a trapper and hunter, doing the same hard physical work as the men around her. She didn’t come to prove anything. She came because she belonged.

Christiane Ritter overwintered here in the 1930s and wrote A Woman in the Polar Night, one of the most honest accounts of what darkness, isolation, and dependence on others can do to a human being. Her writing is not heroic-it is observant. She describes fear, wonder, boredom, and the slow reshaping of identity when nature sets the schedule.

And Hanna Resvoll-Holmsen, Norway’s first female botanist, conducted pioneering scientific work in Svalbard in the early 1900s. She mapped fragile Arctic plant life with extraordinary care, understanding that noticing precisely is an act of protection. Much of Svalbard’s conservation ethic traces back to her work.

These women didn’t conquer Svalbard. They adapted to it. They stayed. They wrote about it and inspired many, including myself.

Ice That Holds Everything Together

In Svalbard, ice is not just something you admire from a distance. It is something you rely on.

Sea ice determines where you can travel. Glacier fronts shape fjords. Snowpack determines safety. Movement happens only when conditions allow it. I learned to read ice the way my father once read weather charts-slowly, conservatively, knowing that getting it wrong carries consequences.

Svalbard sits at the receiving end of the North Atlantic Current, an extension of the Gulf Stream that brings relatively warm water north. That current is the reason Svalbard’s climate is milder than other places at the same latitude. But it is also why Svalbard is changing so quickly.

Roughly 90% of the excess heat from global warming is absorbed by the oceans. That heat is delivered directly to Svalbard’s doorstep. As a result, Svalbard is warming at approximately four times the global average, making it one of the fastest-changing places on the planet. You see it in thinner sea ice, rain-on-snow events, destabilized permafrost, and shifting wildlife behaviour.

Living and working here, you’re constantly aware that this place matters far beyond its borders. Institutions like UNIS (The University Centre in Svalbard) and the Norwegian Polar Institute are based here because conditions are measurable, changes are visible, and long-term data matters. You feel the weight of that responsibility simply by being present.

Svalbard is not just a witness to climate change. It is an early warning system. All the more reason to experience this for yourself.

The Blue Light

This time of year, Svalbard enters a period many people describe as the blue light season. It is my most impactful season.

Factually, it is prolonged twilight —when the sun remains below the horizon but close enough that its light scatters through the atmosphere at a shallow angle. Shorter blue wavelengths dominate, bathing the landscape in deep cobalt and steel-blue tones. Because of Svalbard’s latitude, this light lingers. It doesn’t pass quickly.

Standing in that blue light feels almost unreal, like being folded into the landscape itself. Ice, mountains, sky, and sea seem to sit on the same plane, and you are suddenly part of it rather than observing it. It’s not calming in a soft way-it’s absorbing.

Painters like Norwegian Kåre Tveter spent their lives trying to capture this quality of light. Being inside it, I understand why.

You feel held by this amazing magnetic energy, and even in summer, under the midnight sun, there is no real edge between day and night. You stop rushing. You begin to notice. It is truly a transformational experience, hard to articulate, though I try.

Wildlife on its own terms

Wildlife in Svalbard is not there just for our experience. We are there as guests and hopeful protectors.

A polar bear track crossing your route changes your plan immediately. That is not fear, it is information. Svalbard’s strict travel and firearm regulations exist because humans are visitors in a functioning predator ecosystem.

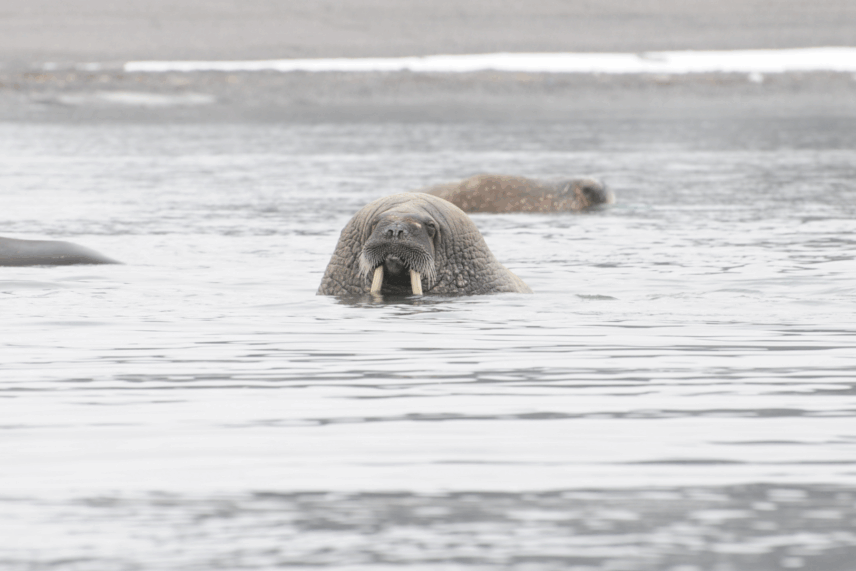

Svalbard reindeer move with remarkable efficiency, conserving energy in a land of scarcity. Arctic foxes appear and disappear like punctuation marks across the tundra. Nothing wastes movement here. Arctic terns, puffins, walruses. Adaptation is visible.

You are not the main character. And that truth is actually pretty humbling.

Rockets Over the Arctic

In 2021, as part of our 19-month Arctic Expedition, we were on standby for more than three weeks to record a rocket launch, positioned in one of the few places on Earth with no ambient light, waiting. We knew a rocket launch was possible. We just didn’t know when.

Then the message came through on the satellite phone: Ready to launch in seven minutes.

We moved fast, knowing there would be no second chance. Standing beneath an aurora-lit sky, we watched a NASA rocket release barium gasses triggering one of the most extraordinary light displays I’ve ever witnessed. The upper atmosphere responded instantly-colour, motion, energy-everything alive at once.

We weren’t just watching. We were recording conditions, timing, and light-exactly what the mission required. The data we captured was later shared with researchers, and we were told, half joking, half serious, that we had earned the title of rocket citizen scientists.

In Svalbard, moments like that don’t feel out of place. Ancient ice, space science, and human presence overlap here in a way that still feels unreal.

Why I Keep Saying Yes to Svalbard

What brings me back, again and again, is a moment I will never forget. March 8th. After three months without sun, it finally crested the mountain range. Not all at once- slowly warming skin that had learned to live without it. You feel gratitude first. Then something deeper settles in. There’s a particular kind of intimacy that grows in Svalbard during that time.

With the returning light. With ice that is never the same from one day to the next. With wildlife that appears only on its own terms. You don’t chase these moments. You receive them.

There is something about this place that feels like it holds you – quietly, without asking for anything in return. And once you’ve felt that, all you want to do is hold it back. Pay attention. Protect it. Show up for it with care and responsibility.

That is why I love Svalbard, Norway. And why I keep coming back. Again and again.

Join our Polar Ambassador, Sunniva Sorby, on our June 2026 Svalbard Explorer small ship expedition with Wild Women Expeditions.